Table of Contents

The Beginning

The First Federal Law Enforcement Agency

The U.S Marchal’s Bloodline

The Establishment of the Legislative Law Enforcement Agency

The U.S Capital Police Bloodline

Act for the Preservation of the Public Peace within the District of Columbia (1828)

Capitol Police Administrative Technical Corrections Act of 2009

The management Evolution of the U.S. Capitol Police:

Background

The Art of the Steal— We know our elections were stolen. So, how exactly were they stolen? What if I told you that our elections were compromised at multiple levels and in various phases? They knew we were catching on to their usual tactics, so they introduced additional safeguards. One such measure involved the mail-in ballots, prompted by the fabricated COVID pandemic. It may not be widely accepted now, but soon we are likely to discover facts that confirm what many already suspect—that COVID was strategically used to prevent Trump from becoming president. They couldn't put all their eggs in one basket, knowing We The People, were on to them. Initially, many of us fell for the COVID narrative, but it didn’t take long to perceive it as an overreach by the federal government.

Why fabricate COVID? The goal was to establish a more robust and thorough mail-in ballot system, and to instill enough fear that people would choose to mail their ballots rather than vote in person. This strategy was one of the national-level manipulations they implemented. Another layer of deceit involved mail-in ballots at the local level, enabling manipulation of the vote counts, as widely observed. On the state level, the tactics were glaring with halted vote counts, middle-of-the-night ballot surges, and a lack of transparency with inadequate oversight from both party representatives. Additional methods included boarding up windows at polling stations, frivolous lawsuits and expelling watchers from the opposing party. This constituted the state-level fraud and cheating.

But there was yet another safeguard at the national level: the certification of electors. Vice President Pence had ample constitutional opportunities to decertify electors based on the irregularities observed at both local and state levels. However, what transpired on January 6th was an absolute distortion of events, destined to be recorded in American history as the most extensive subversion of the people’s electoral choice ever witnessed. 'The Art of the Steal' series will delve deeply into these events.

But first, consider this: What is the most powerful position in our federal government? Is it the president? Reflect on that as we proceed.

Introduction

We can no longer afford to delay in revealing the truth about the 2020 election and the events of January 6th. Uncovering the multiple points of failure that have obscured the truth is critical, as these insights are vital for the survival of our nation. The need for an unprecedented overhaul of our federal government institutions, particularly our federal law enforcement and justice system network spanning all three branches of government, cannot be overstated. I aim to expose the profound deficiencies and failings within our federal law enforcement agencies, which are likely to astonish as much as they have alarmed me.

The extent of the systematic breakdown is overwhelming, and the solution does not lie with these faltering institutions—it rests with us, We the People. We must take it upon ourselves to save, correct, and revamp our institutions and provide the necessary oversight, because it's clear that no one else will. Any aspect of the federal government can be reoriented towards constitutional principles. The idea of drafting a new constitution, however, is unrealistic, unfeasible, and illogical. Dismantling our current system to construct a new one, especially when we face challenges in repairing the existing framework, would be imprudent. Such an approach would likely lead to even greater failures. Instead, we should focus on reinforcing our current constitutional structure, ensuring it aligns with its foundational principles and effectively addresses today’s challenges.

This might seem extreme, but consider this: are we not perilously close to a point of irreparable damage? I believe we're not there yet, but alarmingly close. The 2020 elections and the January 6th incident should serve as a clarion call, illuminating their complexities and failures. From these failures, we can learn valuable lessons. Yet, there seems to be a deliberate obfuscation of information that, while publicly available, remains hidden. This might initially seem paradoxical, but further explanation will clarify the reality of this situation. The discoveries I've made in my research are consistently buried under the debris of our information-saturated era.

Our elections were compromised at every governmental level—local, state, and national—each playing a pivotal role in the usurpation of our leadership selection. Reflect on this: our elections were compromised because we permitted it. Corruption thrives on ignorance and a lack of awareness. As Thomas Jefferson frequently pointed out, the foundation of corruption, government overreach, and human rights violations is the ignorance of the populace. The only way out of our current predicament is through education, understanding our governmental system, engaging with it, and ensuring our leaders are held accountable and to enforce transparency. The alternative is a path marked by violence, bloodshed, and extensive loss of life, which I firmly reject in favor of becoming politically astute and proactive rather than resorting to violence.

We face deep-seated issues within our institutions that require urgent reform. However, prioritization is crucial. In my view, if our federal law enforcement and the Department of Justice are corrupt, dysfunctional, and ineffective at safeguarding human rights, then any reforms at other levels of governance are doomed to fail. We must learn to initiate local actions that have national repercussions, particularly focusing on our law enforcement agencies at all levels. Upon deep reflection and analysis, I've concluded that adherence to the rule of law and the Constitution has drastically declined.

In this series, we'll examine the systemic failures through case studies of the 2020 elections and the January 6th incident, which was not an insurrection but rather a "fed-surrection," as discussed in the last AlphaWarriorShow podcast with Ivan Raiklin. To begin this examination, let’s start where Ivan Raiklin and Alpha Warrior did, focusing on the law enforcement agencies within our government. It's essential to reform these before addressing other institutions known to be fractured and hemorrhaging, such as Health and Human Services, Child Protective Services, child welfare, and immigration. We cannot hope to reform if the rule of law is subverted, broken, and ineffective. Our law enforcement institutions and the rule of law should be a shield for the American people, not a weapon wielded against us by the government we elected and empowered.

The Beginning

The U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1788, established the framework for the federal government, dividing it into three branches to ensure a balance of power: the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. This separation of powers is detailed in the first three articles of the Constitution.

Article I

Establishes the Legislative Branch, consisting of the House of Representatives and the Senate, collectively known as Congress. Congress is granted the power to make laws, levy taxes, declare war, and regulate interstate and international commerce. It also holds the power to oversee the other two branches of government.

Article II

Sets up the Executive Branch, headed by the President of the United States. The President is tasked with enforcing the laws written by Congress and is granted authority to appoint Cabinet officials, negotiate treaties, direct military operations, and ensure that the laws are faithfully executed.

Article III

Creates the Judicial Branch, which includes the Supreme Court and other federal courts that the Congress might establish. This branch is responsible for interpreting the laws and the Constitution, resolving disputes under federal law, and determining the constitutionality of laws.

Within these branches, specific provisions relate to the enforcement of laws and justice. Notably, the Constitution does not explicitly detail a comprehensive federal law enforcement structure as we know it today. Instead, it provides the basis for such a structure through the powers granted mainly to the executive branch.

The First Federal Law Enforcement Agency

The first federal law enforcement entity was the United States Marshals Service, established in 1789 by the Judiciary Act signed by President George Washington. The Marshal’s Service was created to support the federal courts within their judicial districts and to carry out all lawful orders, including serving warrants, apprehending fugitives, and managing assets seized from criminals. The creation of this agency was essential due to the need for a practical mechanism to enforce federal laws and court orders, reflecting the early challenges of governance in a nation without established federal administrative structures outside of major cities.

The establishment of the United States Marshals Service in 1789 is a prime example of how the Constitution enables the creation of federal law enforcement entities through the interplay of the legislative and executive branches, with some involvement from the judicial branch.

Legislative Branch

The U.S. Marshals Service was established by the Judiciary Act of 1789, which was passed by Congress. This act was one of the first pieces of legislation enacted by Congress under its constitutional authority to create federal courts and establish their jurisdiction, as outlined in Article III of the Constitution.

The Judiciary Act of 1789 not only established the federal court system but also created the office of the U.S. Marshal. The act specified that a U.S. Marshal should be appointed for each federal judicial district and outlined their primary duties, which included:

Serving writs, summonses, and other process issued by federal courts.

Making arrests and handling prisoners.

Attending court sessions and maintaining order.

Executing the lawful orders and judgments of the courts.

By passing the Judiciary Act, Congress exercised its constitutional power to create laws necessary for the establishment and functioning of the federal government, including the creation of a federal law enforcement entity to support the newly formed federal court system.

Executive Branch

While Congress created the office of the U.S. Marshal through legislation, the actual appointment of individual marshals falls under the authority of the executive branch. As outlined in the Judiciary Act, U.S. Marshals were to be appointed by the President, with the advice and consent of the Senate.

This appointment process is consistent with the President's executive power under Article II of the Constitution, which grants the President the authority to appoint officers of the United States, including those in law enforcement roles. Once appointed, U.S. Marshals fall under the supervision of the executive branch and are responsible for carrying out the President's constitutional duty to "take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed."

Judicial Branch

Although the judicial branch is not directly involved in the creation or appointment of U.S. Marshals, it does play a role in their oversight and utilization. As outlined in the Judiciary Act, U.S. Marshals are assigned to specific federal judicial districts and are responsible for carrying out the orders and judgments of the federal courts within those districts.

In this capacity, U.S. Marshals act as an enforcement arm of the federal judiciary, ensuring that the courts' decisions are carried out and that the rule of law is upheld. The courts also have the authority to hold U.S. Marshals accountable for any misconduct or failure to carry out their duties properly.

The U.S Marchal’s Bloodline

The establishment of the United States Marshals Service in 1789 demonstrates how the Constitution enables the creation of federal law enforcement entities through the interplay of the three branches of government. Congress, using its legislative powers, created the office of the U.S. Marshal; the President, through executive authority, appoints individual marshals; and the federal courts utilize and oversee the marshals in carrying out their judicial functions. The Judiciary Act of 1789, also known as "An Act to Establish the Judicial Courts of the United States," was a foundational piece of legislation that established the structure of the federal court system. While the Act has been amended and supplemented over time, many of its core provisions remain in effect today. Here is the bloodline of this Act to date. This will be an important concept to understand as we progress through the series;

Judiciary Act of 1789:

Established the basic structure of the federal judiciary, including the Supreme Court, district courts, and circuit courts.

Created the office of the U.S. Marshal and the positions of Attorney General and U.S. Attorneys.

Judiciary Act of 1801 (Midnight Judges Act):

Reduced the size of the Supreme Court and established new circuit courts.

Passed by the Federalist-controlled Congress in the final days of John Adams' presidency.

Largely repealed by the subsequent Democratic-Republican Congress in 1802.

Judiciary Act of 1802:

Repealed the Midnight Judges Act and restored the structure of the federal judiciary to its pre-1801 state.

Judiciary Act of 1869:

Established nine judicial circuits and provided for the appointment of circuit judges.

Reduced the Supreme Court's circuit-riding duties.

Evarts Act of 1891 (Circuit Courts of Appeals Act):

Established the Circuit Courts of Appeals as intermediate appellate courts between the district courts and the Supreme Court.

Relieved the Supreme Court of most of its remaining circuit-riding duties.

Judicial Code of 1911:

Codified and reorganized the existing laws related to the federal judiciary.

Abolished the old circuit courts, transferring their jurisdiction to the district courts and the Circuit Courts of Appeals.

Judiciary Act of 1925 (Judges' Bill):

Gave the Supreme Court greater control over its docket by making most of its jurisdiction discretionary through the writ of certiorari.

Judicial Code of 1948 (Title 28 of the U.S. Code):

Comprehensive reorganization and codification of the laws relating to the federal judiciary.

Replaced the Judicial Code of 1911 and remains the primary governing law for the structure and operation of the federal court system today.

This bloodline shows how the federal judiciary has evolved over time through a series of legislative acts, each building upon and modifying the structure established by the Judiciary Act of 1789.

As the federal judiciary evolved through the Judiciary Act of 1789 and subsequent legislative acts, the need for a dedicated law enforcement entity to protect the U.S. Capitol and its occupants became increasingly apparent. The U.S. Marshals Service, established by the Judiciary Act of 1789, played a crucial role in enforcing federal laws and ensuring the security of the federal courts. However, the unique challenges of safeguarding the nation's legislative branch called for a specialized force.

The Establishment of the Legislative Law Enforcement Agency

In 1828, recognizing the growing need for a dedicated security presence at the U.S. Capitol, President John Quincy Adams signed the "Act for the Preservation of the Public Peace within the District of Columbia." This seminal legislation authorized the hiring of four officers to protect the U.S. Capitol Building and its grounds, marking the birth of the U.S. Capitol Police. Just as the Judiciary Act of 1789 laid the foundation for the federal judiciary and the U.S. Marshals Service, the Act of 1828 established the groundwork for a separate, specialized law enforcement agency tasked with protecting the heart of our American Republic.

The establishment of the U.S. Capitol Police in 1828 highlights the critical need to ensure the safety and security of the legislative branch, especially during pivotal events like the certification of presidential elections. However, the events of January 6th, 2021, raise important questions about the role and placement of this law enforcement entity within the legislative branch. While the Capitol Police are indispensable for the protection of Congress members, the occurrences on that day prompt a reevaluation of whether its integration into the legislative branch is entirely appropriate or effective.

As the nation continues to process the implications of these events, it is crucial to delve into the historical context and development of the U.S. Capitol Police, and to contemplate the optimal way for this unique body to continue fulfilling its duties amidst evolving threats and challenges to our Constitutional Republic.

The primary law that established the Capitol Police was the "Act for the Preservation of the Public Peace within the District of Columbia" of 1828. Over time, several other acts and statutes have further defined and expanded the role of the Capitol Police, including:

The Capitol Police Act of 1867, which formally recognized the Capitol Police as a separate entity from the Metropolitan Police Department of Washington, D.C.

The Capitol Police Jurisdiction Act of 1992, which expanded the agency's jurisdiction to include areas beyond the Capitol grounds.

The Capitol Police Administrative Technical Corrections Act of 2009, which made various administrative and technical changes to the agency's governing laws.

The creation of the Capitol Police was primarily a response to the need for dedicated security for the U.S. Capitol Building and its grounds. In the early 19th century, there were growing concerns about crime and disorder in Washington, D.C., and the need for a specialized force to protect the seat of the federal government became apparent. The establishment of the Capitol Police was part of a broader effort to ensure the safety and security of Congress and its facilities.

Initially, the Capitol Police was overseen by the Commissioner of Public Buildings, who was appointed by the President. In 1849, oversight of the agency was transferred to the Sergeants at Arms of the House and Senate. This dual oversight structure remained in place until 1867, when the Capitol Police Act placed the agency under the sole authority of the Sergeants at Arms.

The Establishment of the District of Columbia

The Organic Act of 1871, also known as the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1871 or the Act to provide a Government for the District of Columbia, did have an impact on the U.S. Capitol Police, although indirectly.

Prior to 1871, the District of Columbia was governed by separate charters for the cities of Washington and Georgetown, as well as a county government for the rural areas. The Organic Act of 1871 repealed these charters and established a new, unified government for the District of Columbia. This new government was headed by a governor appointed by the President and a legislative assembly elected by the citizens of the district.

While the act did not directly address the U.S. Capitol Police, it did change the governance structure of Washington, D.C., which had implications for law enforcement in the city. The Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia, which had been established in 1861, was placed under the authority of the new district government.

However, the U.S. Capitol Police remained a separate entity, dedicated to the protection of Congress and its facilities. The Capitol Police continued to operate under the authority of the Sergeants at Arms of the House and Senate, as established by the Capitol Police Act of 1867.

Capital Police Operational Framework

Based on the provided legal text, here is a summary of the relevant information about the Capitol Police:

Duties and responsibilities:

The Capitol Police are responsible for policing the United States Capitol Buildings and Grounds under the direction of the Capitol Police Board (§1961(a)).

They have the duty to prevent any portion of the Capitol Grounds and terraces from being used as playgrounds or otherwise, to protect the public property, turf, and grass from destruction or injury (§1963).

The Capitol Police are authorized to protect any Member of Congress, officer of the Congress, and any member of their immediate family, in any area of the United States, if the Capitol Police Board determines such protection to be necessary (§1966(a)).

The Capitol Police shall perform a threat assessment for former Speakers of the House of Representatives, and if warranted, provide a protective detail for a period of not more than one year beginning on the date they leave such office (§1966a).

The Capitol Police may request assistance from Executive departments and agencies in the performance of its duties (§1970(a)(1)).

The Capitol Police are responsible for policing the Capitol buildings and grounds.

Special privileges or powers:

The Capitol Police have the power to enforce specific provisions and make arrests within the United States Capitol Buildings and Grounds for violations of any law of the United States, the District of Columbia, or any State, or any regulation promulgated pursuant thereto (§1961(a)).

They have additional authority to make arrests within the District of Columbia for crimes of violence committed within the Capitol Buildings and Grounds and to make arrests, without a warrant, for crimes of violence committed in the presence of any member of the Capitol Police performing official duties (§1961(a)).

In the performance of their protective duties, members of the Capitol Police are authorized to make arrests without warrant for any offense against the United States committed in their presence, or for any felony cognizable under the laws of the United States if they have reasonable grounds to believe that the person to be arrested has committed or is committing such felony (§1966(c)).

The Capitol Police have the authority to make arrests and enforce laws within specific areas of the District of Columbia, including within the United States Capitol Grounds, and in the presence of a member if the member is performing official duties when a crime of violence is committed (§1967(a)).

In the event of an emergency, as determined by the Capitol Police Board, a concurrent resolution of Congress, or the Chief of the Capitol Police, the Chief may appoint law enforcement officers from Federal, State, or local government agencies and members of the uniformed services to serve as special officers of the Capitol Police within their authorities in policing the Capitol buildings and grounds (§1974(a)).

In the event of an emergency, the Chief of the Capitol Police may appoint law enforcement officers from any Federal, State, or local government agency, as well as members of the uniformed services, to serve as special officers of the Capitol Police (§1974(a)).

The Chief of the Capitol Police can consider, determine, and settle claims for money damages against the United States caused by the negligent or wrongful act or omission of any employee of the Capitol Police while acting within the scope of their employment (§1977(a)(1)).

Authority and jurisdiction:

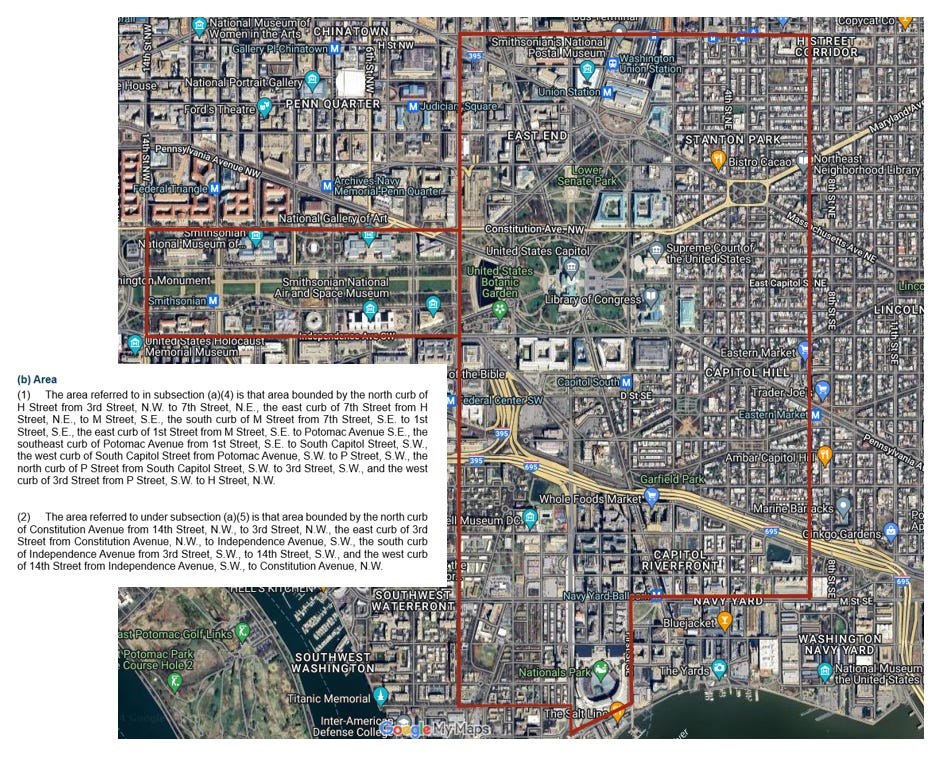

The Capitol Police's jurisdiction covers the United States Capitol Buildings and Grounds, which include any building or facility acquired by the Sergeant at Arms of the Senate or the Chief Administrative Officer of the House of Representatives for the use of the Senate or the House, respectively, for which an agreement has been entered into with the United States Capitol Police for policing (§1961(b), (c)).

Their jurisdiction also extends to the Library of Congress buildings and grounds, with the authority granted to the relevant police force in cases of buildings or grounds not located in the District of Columbia (§1961(d)).

The Capitol Police's authority to make arrests and enforce laws extends to specific areas within the District of Columbia, as described in §1967(b)(1) and (2).

The Capitol Police Board has exclusive charge and control of the regulation and movement of all vehicular and other traffic within the United States Capitol Grounds (§1969(a)).

Special officers appointed under §1974 serve within the authorities of the Capitol Police in policing the Capitol buildings and grounds (§1974(a)).

The Capitol Police have jurisdiction over the Capitol buildings and grounds, as established by law (§1978(a)).

Limitations or restrictions on their power:

The Metropolitan Police force of the District of Columbia is authorized to make arrests within the United States Capitol Buildings and Grounds for violations of laws or regulations. However, this authority does not allow them to enter such buildings to make arrests in response to complaints, serve warrants, or patrol the United States Capitol Buildings and Grounds without the consent or request of the Capitol Police Board (§1961(a)).

The authority granted to the Capitol Police does not affect the authority of the Metropolitan Police force of the District of Columbia with respect to the areas described in §1967(b) (§1967(c)).

No services, equipment, or facilities may be ordered, purchased, leased, or otherwise procured for the purposes of carrying out the duties of the Capitol Police by persons other than authorized officers or employees of the Federal Government (§1970(a)(2)).

No funds may be expended or obligated for the purpose of carrying out §1970, other than funds specifically appropriated to the Capitol Police Board or the Capitol Police for those purposes, with some exceptions (§1970(a)(3)).

Special officers appointed by the Chief of the Capitol Police serve without pay (other than pay received from their employing agency) and for a specified period (§1974(b)).

The Chief of the Capitol Police must notify and obtain approval from specific Congressional committees before deploying any officer outside of their established jurisdiction, except in cases of responding to imminent threats or emergencies, intelligence gathering, or providing protective services (§1978(a), (b)).

The release of security information by the Capitol Police to another entity is subject to the determination of the Capitol Police Board, in consultation with other law enforcement officials, security experts, and appropriate Congressional committees (§1979(b)).

Oversight and accountability mechanisms:

The Capitol Police operate under the direction of the Capitol Police Board, consisting of the Sergeant at Arms of the United States Senate, the Sergeant at Arms of the House of Representatives, and the Architect of the Capitol (§1961(a)).

The design and installation of security systems for the Capitol buildings and grounds are carried out under the direction of the Committee on House Oversight of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate (§1964(b)).

Maintenance of security systems for the Capitol buildings and grounds is carried out under the direction of the Committee on House Oversight of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate (§1965(a)).

The Capitol Police's authority to protect individuals is subject to the direction of the Capitol Police Board (§1966(a)).

Regulations governing the Capitol Police's authority are prescribed by the Capitol Police Board and approved by the Committee on House Oversight of the House of Representatives and the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate (§1967(a)).

The Capitol Police Board is responsible for promulgating and enforcing regulations related to vehicular and other traffic within the United States Capitol Grounds (§1969(a), (b)).

Before making a request for assistance, the Capitol Police Board shall consult with appropriate Members of the Senate and House of Representatives in leadership positions, except in an emergency (§1970(a)(1)).

The Capitol Police Board may revoke a request for assistance provided under §1970(a)(4)(B)(ii)(III) upon consultation with appropriate Members of the Senate and House of Representatives in leadership positions (§1970(a)(5)).

Executive departments and agencies providing assistance must submit a report detailing expenditures to the Chairman of the Capitol Police Board, who then submits a summary to the Committees on Appropriations of the Senate and the House of Representatives (§1970(b)).

The Capitol Police Board may prescribe regulations to carry out §1974, subject to approval by the Speaker of the House and the Majority Leader of the Senate, in consultation with their respective Minority Leaders (§1974(d)).

The Capitol Police Board may prescribe regulations for the appointment of special officers, subject to approval by the Speaker of the House and the Majority Leader of the Senate (§1974(d)).

For claims made by Members of Congress or Congressional employees, the Chief of the Capitol Police must notify the Chairman of the applicable Committee and submit a proposal for resolution, subject to the Chairman's approval (§1977(a)(2)).

The Capitol Police Board may promulgate regulations to carry out the section on the release of security information, with the approval of the Senate Committee on Rules and Administration and the House Committee on House Administration (§1979(d)).

Additional information:

The use of funds to install permanent, above-ground fencing around the perimeter, or any portion thereof, of the United States Capitol Grounds is prohibited (§1965a).

The U.S Capital Police Bloodline

Today, the Capitol Police is overseen by the Capitol Police Board, which consists of the Sergeants at Arms of the House and Senate, as well as the Architect of the Capitol. The Chief of the Capitol Police reports to the Board and is responsible for the day-to-day management of the agency.

The "bloodline" of acts and management structure related to the Capitol Police includes:

Act for the Preservation of the Public Peace within the District of Columbia (1828)

Management: The Capitol Police was initially overseen by the Commissioner of Public Buildings, who was appointed by the President.

Capitol Police Act of 1867

· Management change: The act placed the Capitol Police under the sole authority of the Sergeants at Arms of the House and Senate, removing oversight from the Commissioner of Public Buildings.

Capitol Police Jurisdiction Act of 1992

Management: The Capitol Police remained under the authority of the Sergeants at Arms of the House and Senate.

Note: This act primarily focused on expanding the agency's jurisdiction to include areas beyond the Capitol grounds and did not significantly alter the management structure.

Capitol Police Administrative Technical Corrections Act of 2009

Management: The act maintained the Capitol Police under the authority of the Capitol Police Board, which consists of the Sergeants at Arms of the House and Senate, as well as the Architect of the Capitol. The Chief of the Capitol Police reports to the Board and is responsible for the day-to-day management of the agency.

Note: While this act made various administrative and technical changes to the agency's governing laws, it did not fundamentally alter the management structure established by the Capitol Police Act of 1867.

The management Evolution of the U.S. Capitol Police:

1828-1867: Overseen by the Commissioner of Public Buildings, appointed by the President.

1867-Present: Under the authority of the Sergeants at Arms of the House and Senate.

2009-Present: Managed by the Chief of the Capitol Police, who reports to the Capitol Police Board, consisting of the Sergeants at Arms of the House and Senate, and the Architect of the Capitol.

This evolution of the management structure reflects the ongoing efforts to ensure effective oversight and governance of the U.S. Capitol Police as its role and responsibilities have expanded over time. These acts, along with various other statutes and appropriations bills, have shaped the development and evolution of the U.S. Capitol Police over its history.

The Constitutional Conflict

The Constitution establishes distinct roles for the executive and legislative branches, with the executive responsible for enforcing laws and the legislative tasked with creating them. This separation of powers is designed to ensure that each branch is equipped with the necessary safeguards to carry out its primary functions effectively and accountably.

Law enforcement entities within the executive branch, such as the FBI, are subject to multiple layers of accountability and oversight. These include supervision by the Department of Justice, judicial review of their actions, and congressional oversight. This multi-tiered system of checks and balances helps to prevent abuse of power and ensure that law enforcement agencies operate within the bounds of the law.

In contrast, the legislative branch is structured to ensure accountability in the process of writing and passing laws. However, it lacks the same robust oversight mechanisms for enforcing laws, as this falls outside its primary constitutional role. The current situation with the U.S. Capitol Police, which operates under the jurisdiction of the legislative branch, highlights the potential risks associated with this arrangement.

The events of January 6th, 2021, at the U.S. Capitol have exposed the limitations and challenges of having a law enforcement agency under the control of the legislative branch. The response to the incident and the subsequent investigations have been marred by allegations of political influence, inconsistencies in testimony, and a lack of transparency. This has led to a erosion of public trust in the impartiality and effectiveness of the U.S. Capitol Police.

These issues underscore the need to realign the U.S. Capitol Police with the constitutional principles of separation of powers and the executive branch's responsibility to enforce laws. By placing the agency under the jurisdiction of the executive branch, it would be subject to the same accountability mechanisms and oversight as other federal law enforcement agencies, such as the FBI.

This change would help to ensure that the U.S. Capitol Police operates impartially, free from undue political influence, and in accordance with established protocols and standards. It would also facilitate better coordination and communication with other federal law enforcement agencies, as well as access to necessary resources and expertise.

Moreover, the move would enhance the transparency and accountability of the U.S. Capitol Police, as it would be subject to the same reporting requirements and oversight measures as other executive branch law enforcement agencies. This, in turn, would help to rebuild public trust in the agency and demonstrate its commitment to upholding the rule of law.

The events of January 6th, 2021 have exposed the constitutional crisis that arises when a law enforcement agency operates under the control of the legislative branch. To address this issue and ensure the impartial, effective, and accountable enforcement of laws, it is necessary to place the U.S. Capitol Police under the jurisdiction of the executive branch. This realignment would safeguard the separation of powers, enhance oversight and accountability, and ultimately, better serve the interests of the nation and its citizens.

The Fed-Surrection

As previously discussed in relation to the legislative branch and the Capitol Police, we examined the framework under which they operate, as specified in Title 2 Chapter 29. This discussion detailed the roles, responsibilities, and the significant authority that the U.S. Capitol Police possess under codified law. In an episode of the AlphaWarriorShow featuring Ivan Raiklin, he described what he termed a "fed-surrection," a parliamentary coup orchestrated by Nancy Pelosi and Mitch McConnell. During the podcast, Ivan claimed that Pelosi managed to obscure the disruptions that occurred during the counting of electors on January 6th. With what we now know about the capitol police and it's overwhelming amount of power, the possibility that this was the case is overwhelmingly possible. During that podcast Ivan detailed out a plan of action that could have been taken by then Vice President Pence. What we saw Vice President Pence do was the opposite. The question is, why did he not carry out this plan? There's a lot of questions that January 6th produced that are unanswered. It is my hopes that with extensive research and understanding Ivans perspective perhaps we can get some of those questions answered. To give you an understanding as to what that plan was, below are the main bullet points that we will be covering in the next few parts of this series. The following are bullet points from AlphaWarriorShow by Ivan Raiklin;

Contact Kevin McCarthy (Leader of the Republican Party controlling the state delegation vote) and Mark Short (Mike Pence’s Chief of Staff) to communicate the strategy of objecting by state delegations, which would trigger a contingent election and potentially lead to the reelection of Trump.

The strategy relies on the framework of the Electoral Count Act and the 12th Amendment where, in the absence of specific guidance on how to vote on objections of electors by the House, it would default to the House deciding the procedure.

The 12th Amendment specifies that in a contingent election, the vote should be one state, one vote.

Upon the objections being raised by Paul Gosar and Ted Cruz, and as soon as they broke out into their respective chambers, Kevin McCarthy should call a vote under the state delegation framework.

If Democrats decided not to participate, it wouldn’t affect the outcome due to the quorum requirement which only needs two-thirds of the states to be present, i.e., at least one member from 34 states.

Theoretically, even if only Republicans voted, the vote could be 43 states to zero under the state delegation framework, because 43 of the 50 states had at least one Republican representative to form the state delegation.

Anticipate and counteract potential moves by Nancy Pelosi to disrupt the vote, such as ordering the Sergeant at Arms to evict the Senate from the House chambers to prevent the vote from taking place.

If the session resumes and Mike Pence, as the presiding officer, asks about the ruling on Arizona’s electors, McCarthy should assert that the objection was upheld under the state delegation vote.

It would then be up to Pence to decide whether to accept the state delegation vote or the one person, one vote outcome.

Confirm that the presiding officer (Vice President) has the constitutional authority to break any ties regarding the acceptance of electoral votes.

I hope that I interpreted these correctly. Until next time,

Learn your power,

Question everything,

Trust no one, and

Research on your own.

.... how can we expect anything but more lies and coercion from both unelected and elected officials/bureaucrats many of whom never took an oath to the Constitution - let alone filed one with the Secretary?... perhaps that is a good place to start.

The greatest threat to any authoritarian regime, any shadow cabal, any subversive government, is an informed and empowered Public. We affirm our oath to uphold our civic duties in pursuit of a More Perfect Union. This is the way.