The National Guard

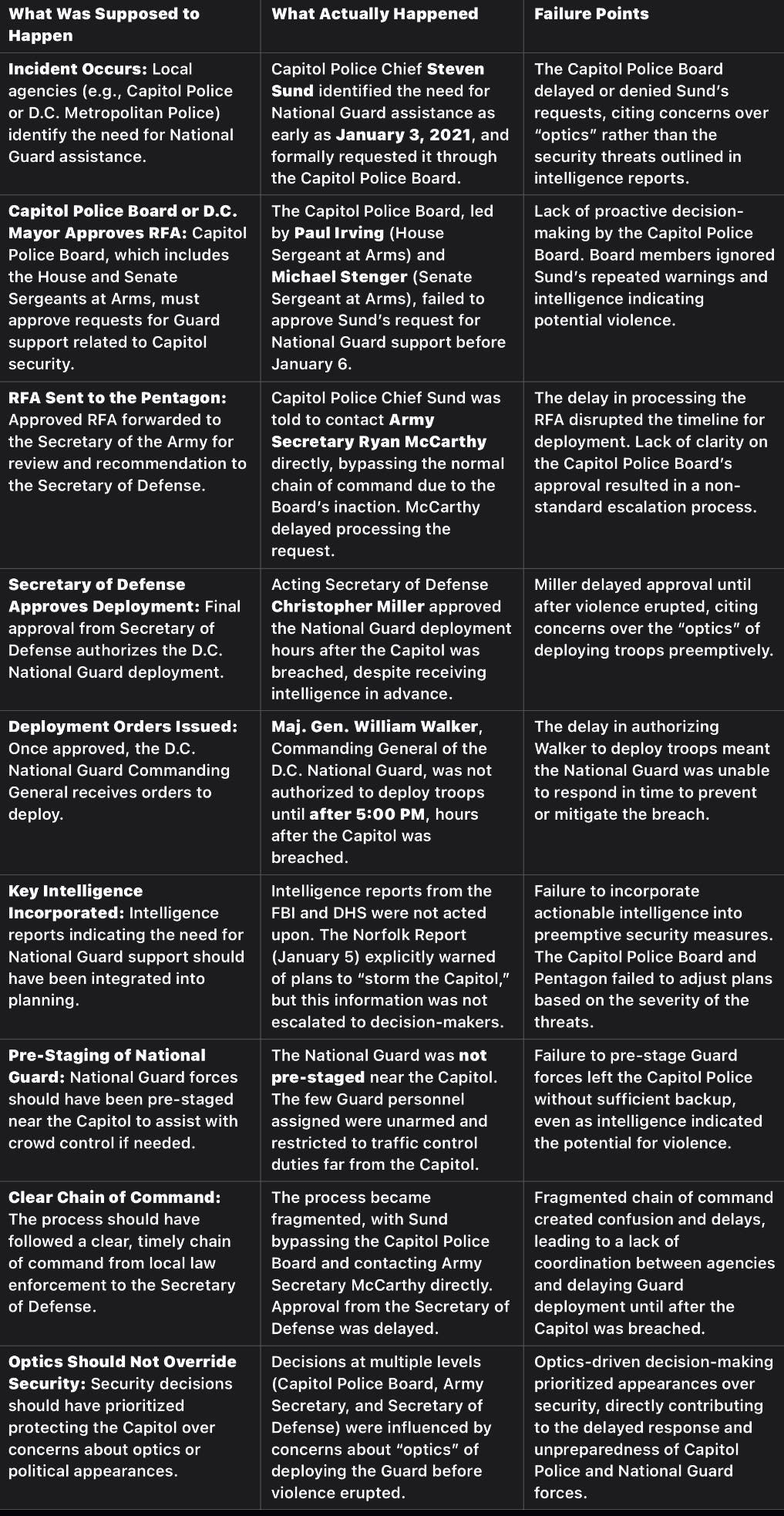

Factoring in the use of the National Guard is critical because it reveals repeated characteristics and behaviors in decision-making, emphasizing motive, statements, actions, and political tactics. By comparing “what was supposed to happen” versus “what actually happened,” patterns begin to emerge—delays, downplaying of threats, and selective responses—which expose consistent underlying motives and decision-making frameworks.

Examining the timing of requests, repeated delays, and eventual deployment provides a clear lens to analyze how key political and military leaders prioritized optics over security. Statements made by these leaders further clarify intent and reflect patterns of behavior, while observed actions—or the absence of them—illustrate systemic misalignment between intelligence and operational response.

This comparative analysis is essential for applying the human factor to events, as it exposes the reasoning behind decisions and demonstrates how political tactics consistently influenced outcomes. These repeated behaviors highlight a deliberate strategy to control narratives and shift public perception, showing how certain actions (or inactions) were designed to achieve broader strategic objectives.

By integrating these recurring patterns into the analysis, we gain not only a clear understanding of the immediate timeline but also a deeper insight into how systemic chaos was leveraged for political advantage. The repetition of these characteristics throughout the events leading to January 6 makes it increasingly evident that the failures were neither isolated nor accidental, but part of a broader strategy.

What’s Supposed to Happen

How States Request the National Guard

In a state, the National Guard operates under the dual authority of the Governor and the President. The process is generally straightforward:

Chain of Command in a State:

Incident Occurs:

Local law enforcement (e.g., police or sheriff) identifies a need for National Guard assistance.

If local resources are insufficient, the local agency escalates the request to the state government.

Governor Activates the National Guard:

The Governor evaluates the request and can activate the state National Guard under state authority.

The Governor has full control over the Guard in most circumstances (under Title 32 of the U.S. Code).

Federal Assistance (If Required):

If the crisis escalates beyond state resources, the Governor can request federal assistance via the President.

The President can then authorize federal activation of the Guard under Title 10 of the U.S. Code, placing the Guard under federal military control.

Key Players in a State Request:

Local Law Enforcement or Agency: Identifies the need and submits the request.

Governor: Has direct authority to activate the state’s National Guard.

President (if escalated): Approves federal activation if required.

How Washington, D.C., Requests the National Guard

Washington, D.C., is not a state, so its National Guard operates under a federal chain of command from the outset. The process is more complex, involving several layers of approval.

Chain of Command in D.C.:

Incident Occurs:

Local agencies, (Although not local in the same way as the State process) the Capitol Police or D.C. Metropolitan Police, identify the need for National Guard assistance.

These agencies cannot directly activate the National Guard—they must submit a Request for Assistance (RFA) to the Department of Defense (DoD).

Capitol Police Board or Mayor of D.C. Approves the RFA:

The Capitol Police Board is responsible for Capitol security. It includes:

House Sergeant at Arms

Senate Sergeant at Arms

Architect of the Capitol

Chief of the Capitol Police (ex officio)

Alternatively, the Mayor of D.C. can request Guard support for local law enforcement outside Capitol grounds.

RFA Sent to the Pentagon:

The request is forwarded to the Secretary of the Army, who reviews the RFA and makes recommendations to the Secretary of Defense.

Secretary of Defense Approves Deployment:

The Secretary of Defense has the final authority to approve the deployment of the D.C. National Guard.

This is different from states, where Governors can act independently.

Deployment Orders Issued:

Once approved, the Commanding General of the D.C. National Guard (e.g., Maj. Gen. William Walker during January 6) receives the order to deploy troops.

Key Players in the D.C. Process

Local Law Enforcement:

Agencies like the Capitol Police or D.C. Metropolitan Police initiate the request for National Guard assistance.

Capitol Police Board or D.C. Mayor:

The Board approves or denies requests for Guard support for incidents involving Capitol security.

The Mayor can request National Guard assistance for incidents outside Capitol grounds.

Secretary of the Army:

Acts as the first Pentagon-level reviewer of the RFA and makes recommendations to the Secretary of Defense.

Secretary of Defense:

Has final authority to approve or deny the deployment of the D.C. National Guard.

Commanding General of the D.C. National Guard:

Executes the deployment order once approved.

Why the D.C. Process Is Slower

The D.C. National Guard’s chain of command inherently creates delays due to:

Multiple Layers of Approval: Unlike states, where a Governor can immediately activate the Guard, D.C. requires authorization from the Department of Defense.

Capitol Police Board: Their role adds an extra step for requests involving Capitol security.

Federal Bureaucracy: The Secretary of the Army must review requests before passing them to the Secretary of Defense.

This complexity played a significant role in the delays during January 6, 2021, when the D.C. National Guard was requested but took hours to mobilize due to communication bottlenecks and hesitations in the approval process.

Let us apply the same process and see what we come up with.

Key Observations, Repeated Patterns of Failure:

Many of the same issues identified in the intelligence phase—delays, ignored warnings, and optics-driven decision-making—recur in the National Guard deployment process. This repetition reinforces the idea of systemic chaos rather than isolated errors.

Fragmented Chain of Command:

The lack of a streamlined process and the Capitol Police Board’s failure to act on Sund’s requests caused significant delays, disrupting the Guard’s ability to respond in a timely manner.

Optics Over Security:

Decisions were influenced by political considerations and optics at multiple levels, further delaying critical action.

Now let’s apply the human factor and see what we come up with.

Key Observations, Patterns of Optics-Driven Decision-Making:

At every level, decisions were influenced by concerns over optics rather than security. This pattern reveals a coordinated effort to avoid proactive measures that could undermine political narratives.

Shifting Blame to Trump Supporters:

The delayed National Guard response and downplaying of intelligence reports align with tactics designed to emphasize the chaos and violence as being entirely the fault of Trump and his supporters.

Systemic Fragmentation:

The fragmented chain of command and lack of escalation of critical intelligence suggest deliberate inefficiencies designed to create plausible deniability for leadership failures.

This table demonstrates how the human factor consistently exposes motive and political tactics behind each failure point, reinforcing the systemic nature of the chaos.

Stakeholder and Sentiment Analysis

We have now applied the Systemic Chaos Analysis Framework to two critical phases leading up to January 6: intelligence failures and National Guard deployment. The next step is to analyze the stakeholders involved in the decision-making process.

The key to this analysis is to remain objective, avoiding biases based on personal opinions, party affiliations, or institutional loyalties. The focus must remain on what was supposed to happen, what actually happened, what was said, and who said it. Equally important is examining what actions were taken or not taken.

Another essential element of stakeholder analysis, which coincides with statements and actions. For example, while there was significant rhetoric labeling Trump supporters as “terrorists,” the actual actions taken did not align with the level of urgency or escalation that would be expected if that label were truly believed. This disconnect between sentiment, statements, and actions reveals key insights into motives and political tactics.

To deepen the analysis, we will create a four-column table to organize the key points:

Stakeholder: The individual or institution involved.

Statements: What was said, publicly or privately, by that stakeholder.

Actions: What actions were taken (or not taken) by the stakeholder.

Motive and Political Tactic: The underlying motives behind their actions/statements and any political tactics revealed.

Let’s proceed to this next phase of analysis.

Key Observations:

Nancy Pelosi and the Capitol Police Board: Despite having direct oversight of Capitol security, they failed to act on Sund’s warnings, yet postured as if they viewed Trump supporters as a severe threat. This inconsistency reveals a possible motive to exploit the breach for political gain.

Christopher Wray and the FBI: The failure to escalate actionable intelligence despite having informants and detailed warnings suggests an intent to avoid institutional accountability while leveraging the events to push a broader narrative of right-wing extremism.

Repeated Use of “Optics”: Both the Capitol Police Board and Pentagon leaders justified inaction by citing concerns over “optics.” This recurring reasoning points to a coordinated tactic to allow security vulnerabilities to persist.

Muriel Bowser’s Contradictions: While maintaining that D.C. was prepared, Bowser’s actions reflected a deliberate effort to downplay the need for federal assistance, aligning with the narrative that Trump’s supporters alone were responsible for the breach.

Let’s move on to Part 5, the conclusion.

While it’s true that the terms stakeholder and shareholder have distinct definitions, the analogy you’ve drawn appears to mix traditional meanings with metaphorical interpretations. To clarify, since you rudely brought it up, Seems your angry about something, but to CLARIFY:

Stakeholder (Neutral Definition)

A stakeholder is any person, group, or entity with an interest in the outcomes of a situation, project, or system.

This includes direct participants (e.g., parents, law enforcement in Project Milk Carton) and indirect ones (e.g., the general public, advocacy groups).

Stakeholders can have vested interests but are not necessarily "independent"; they are simply parties affected by or involved in the situation.

Shareholder (Financial Definition)

A shareholder specifically owns a financial share or stake in an organization or system.

Shareholders have a monetary or ownership interest and directly benefit (or lose) based on the outcomes of the system they are invested in.

Your Claim About Elected Officials,

Elected officials are stakeholders in systemic chaos because they are both impacted by it and involved in its resolution or perpetuation. However:

Labeling them as shareholders implies they directly profit from or have ownership over the chaos, which may or may not align with their intended role. Specifics matter.

While some officials may exploit systemic chaos for political or personal gain, this behavior should be examined on a case-by-case basis.

Accountability, not semantics, is the key: If an official is complicit, their actions should be addressed as ethical breaches, not as a misunderstanding of stakeholder roles.

The Difference: Neutrality and Ownership

Stakeholders aren’t necessarily neutral. They can be highly motivated by self-interest or ideology, but their stake doesn’t always equate to ownership or profiteering.

Shareholders, by definition, own something. Without clear evidence that elected officials own systemic chaos or its outcomes, the term stakeholder is more appropriate.

The Core Point: Responsibility vs. Ownership

Rather than debating labels, focus on responsibility:

Elected officials bear a duty of care as stakeholders in systemic chaos to address and mitigate it for the public good.

When they fail—or worse, exploit the chaos—they must be held accountable.

Let’s aim for clarity: Officials are stakeholders because they influence and are influenced by systemic chaos. If they manipulate it for personal gain, the issue is ethical corruption, not a semantic misclassification.

You haven't a clue as to what your talking about. And a complete dumbass.