Shadows of Power, Part 3

The Restoration of Trust Must Be Measured Against Accountability—And Accountability Is Measured Through the Constitution, Laws, and Operational Integrity

Patriotism Through Accountability

Let me start with this: I am not anti-government. I am not an extremist. I don’t hate our federal agencies, and I don’t despise the framework of our federal government. On the contrary, I believe in the potential for reform—that when held accountable, our institutions can serve the people as they were intended to. I believe in the power of we, the people to initiate meaningful change.

But that change doesn’t come from blind faith or unchecked power. It comes from accountability. It comes from identifying systemic failures and having the courage to demand better. Suggesting that some agencies may need to be radically restructured—or even abolished—is not extremism. It is not hatred of our government. It is patriotism. It is the duty of those who care deeply for this nation to ensure that the government operates within the framework of the Constitution and the law, serving its people—not its own interests.

This isn’t about soundbites, clicks, or attention. It’s not about playing partisan games or stirring controversy for its own sake. These are real issues that require a serious conversation. They demand that we look at what’s happening in our country—the weaponization of government, the erosion of public trust, the targeting of individuals like General Flynn, President Trump and the chaos surrounding January 6. These are not isolated events; they are symptoms of a deeper rot in our institutions that must be addressed.

Let me be clear: reforming these agencies isn’t optional—it’s critical. Accountability isn’t a threat to our republic; it is the backbone of our constitution. It is how we ensure that power remains in the hands of the people and that our government operates with integrity.

Fear won’t save us, and neither will ignorance. We cannot ignore what’s happening simply because it’s easier to look away. The weaponization of our government against its own people is a dangerous precedent, and every day we fail to confront it, we edge closer to losing the freedoms we hold dear. President Trump cannot and should not take this on by himself. We the People must be part of it!

Reform starts with truth. It begins with transparency and a willingness to shine a light on the failures and corruption within our system. These principles aren’t abstract ideals—they are the foundation of meaningful change. Without them, we cannot hope to restore trust, rebuild integrity, or safeguard the future of our republic.

As patriots, it is our responsibility to confront these issues head-on. It’s not an act of extremism to hold our government accountable—it’s an act of patriotism. Reforming what’s broken isn’t an attack on this nation—it’s in defense of it!!

Together, we must demand better, refuse to be silenced, and commit to restoring the integrity of our institutions. This is not just a fight for today—it’s a fight for the future of America.

The measurement of accountability.

The Constitution and Intelligence

The U.S. Constitution provides the foundational framework for how the government addresses intelligence, national security, and related responsibilities. While it does not explicitly mention “intelligence” as a concept, several sections and articles establish the legal basis for intelligence gathering, dissemination, and action, particularly in the realm of domestic operations.

Article II: Powers of the President

Section 1: Vesting Clause

The President’s authority over domestic security stems from the constitutional vesting of executive power. As stated, “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” This grants the President broad powers to direct intelligence operations, particularly in managing domestic threats. The ability to oversee federal law enforcement agencies like the FBI allows the President to lead efforts in preventing terrorism, espionage, and other national security threats.

Section 2: Commander-in-Chief Clause

The Commander-in-Chief Clause further extends the President’s power during times of crisis. According to the Constitution, “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States.” This provision empowers the President to deploy federal resources, including intelligence agencies, to address insurrections, domestic terrorism, and other emergencies. The coordination of entities like the FBI and the National Guard under presidential direction is critical for maintaining order during national crises.

Article I: Powers of Congress

To Provide for the Common Defense and General Welfare

Congress holds the authority to establish laws aimed at addressing domestic threats, though not all legislation unequivocally serves the nation’s best interests. A notable example is the USA PATRIOT Act, which governs domestic surveillance and intelligence sharing. The law’s efficacy came into question on January 6th, 2021.

Was the PATRIOT Act truly inactive that day—or was it misapplied? This clause empowers Congress to create and fund agencies like the FBI and DHS, which handle domestic intelligence. However, the events of January 6th starkly revealed the inadequacies of these agencies during a critical moment. Their apparent inaction raises pressing concerns about operational gaps and systemic failures that allowed the Capitol to descend into chaos.

To Call Forth the Militia

The power to “provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions” underscores Congress’s role in authorizing federal responses to domestic disturbances, including riots, terrorism, or insurrections. This authority forms the legal framework for deploying intelligence and military support to civilian authorities during emergencies.

To Make All Laws Necessary and Proper

The Necessary and Proper Clause grants Congress the flexibility to pass legislation empowering federal agencies to address domestic threats effectively. This authority has led to the establishment of mechanisms like FISA courts, which oversee intelligence surveillance within the U.S., ensuring a balance between national security and civil liberties.

Oversight Authority

Congress maintains constitutional oversight over federal agencies involved in domestic intelligence, exerting influence through bodies like the House and Senate Intelligence Committees. By controlling budgets and appropriations, Congress ensures accountability for agencies like the FBI and DHS, aligning their operations with the nation’s security priorities.

Article III: Judicial Oversight

Section 1: Judicial Power

The Constitution states, “The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” This grants federal courts the authority to oversee and authorize domestic surveillance under laws like the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA). Judges play a crucial role in ensuring intelligence activities comply with constitutional protections by issuing warrants for wiretapping, searches, and other intelligence-gathering operations.

Section 2: Jurisdiction Over Cases Arising Under the Constitution

Federal courts have jurisdiction over cases involving constitutional matters, providing a check on intelligence activities to ensure they do not violate rights such as privacy and due process. The judiciary plays a critical role in resolving conflicts between national security needs and individual liberties.

The Bill of Rights and Limits on Intelligence Practices

First Amendment

The First Amendment protects citizens from surveillance or intelligence operations that infringe on free speech or press freedoms. Courts frequently scrutinize domestic intelligence programs to ensure they do not suppress lawful political dissent or activism, safeguarding individual rights.

Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment guarantees that “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated.” This requires intelligence agencies to obtain warrants before conducting surveillance or searches. It forms the legal basis for laws like FISA, which governs domestic wiretapping and electronic surveillance.

Fifth Amendment

The Fifth Amendment ensures that “no person shall… be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” This protects individuals targeted by domestic intelligence operations, preventing unlawful detentions or actions without judicial oversight.

I know it’s boring, right? But here’s the thing: corruption thrives on ignorance. Corrupt representatives and their questionable practices rely on the fact that most constituents don’t read or understand the laws. If you don’t know what the laws actually say, how can you hold them accountable?

Federal Statutes and Intelligence

Intelligence gathering, sharing, and dissemination within the United States operates under a framework of federal statutes. These laws are essential to understanding where the system succeeds and, more importantly, where it fails. They set the standards for accountability and highlight the gaps that bad actors exploit through loopholes or misinterpretations. Below is a critical analysis of key statutes governing domestic intelligence.

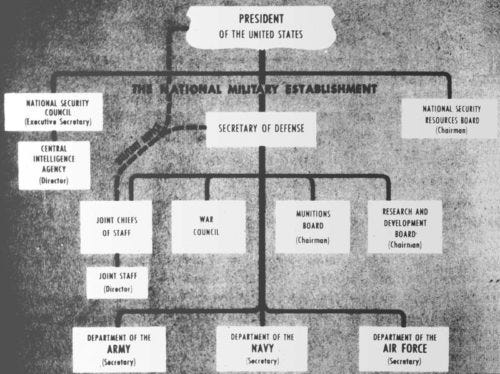

The National Security Act of 1947

This landmark legislation created the modern U.S. intelligence structure, including the establishment of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the National Security Council (NSC), and later, components of the Intelligence Community (IC), such as the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI).

Relevance to Domestic Intelligence: Although the CIA is explicitly restricted to foreign intelligence, this act lays the groundwork for coordination between domestic agencies, like the FBI, and their foreign intelligence counterparts. The NSC provides the President with national security advice informed by intelligence that includes domestic threats.

Intelligence Gathering: The act allows intelligence agencies to collect information domestically but imposes strict guidelines to safeguard civil liberties. Despite these protections, failures in information sharing—like those revealed during 9/11—have prompted reforms.

Dissemination: The act mandates that information collected under its framework balances national security needs with privacy protections. The creation of the ODNI was a response to prior failures, emphasizing cross-agency coordination. However, gaps persist, as demonstrated by events such as January 6th.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) of 1978

FISA governs the surveillance of foreign agents and suspected threats within the United States, establishing the FISA Court to authorize electronic surveillance, physical searches, and data collection.

Relevance to Domestic Intelligence: FISA is pivotal for monitoring foreign threats crossing into domestic spaces, including suspected spies or terrorist cells. However, the law’s application to U.S. citizens has been controversial, raising questions about its oversight and scope.

Intelligence Gathering: Agencies such as the FBI and NSA are authorized to collect data on individuals suspected of acting as foreign agents or engaging in terrorism. However, they must obtain warrants through the FISA Court.

The concept of “incidental collection”—where the surveillance of foreign targets captures communications involving U.S. citizens—has sparked debates over privacy violations.

Dissemination: FISA permits intelligence sharing among federal agencies if deemed relevant to national security. However, abuses in dissemination, such as the unmasking of individuals in intelligence reports, have eroded public trust and exposed the system’s vulnerabilities.

The USA PATRIOT Act (2001)

Passed in the wake of 9/11, the USA PATRIOT Act expanded the government’s surveillance and intelligence-gathering capabilities, ostensibly to bolster counterterrorism efforts. While its intentions were clear, the law’s implementation has raised significant concerns regarding privacy and overreach.

Relevance to Domestic Intelligence: The act lowered barriers between intelligence and law enforcement agencies, enabling them to share information more freely. However, this expanded authority came with substantial risks. The law’s controversial Section 215 authorized bulk data collection, leading to widespread surveillance of American citizens without sufficient oversight.

Intelligence Gathering: Under the PATRIOT Act, the FBI gained the power to issue National Security Letters (NSLs), allowing them to access records without obtaining a court order. The act also broadened the scope of surveillance, enabling the monitoring of electronic communications such as phone calls and internet activity. While these tools aimed to prevent terrorism, they also paved the way for potential abuses of power.

Dissemination: The act emphasized cross-agency intelligence sharing to prevent siloed information, a critical failure identified after 9/11. While this goal was laudable, the lack of safeguards led to significant issues, including over-collection and prolonged data retention. These practices have fueled public distrust and raised questions about the balance between security and privacy.

The Homeland Security Act of 2002

The Homeland Security Act established the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to centralize and streamline efforts to protect the United States from domestic and foreign threats. By consolidating 22 federal agencies, the act sought to create a unified front against emerging dangers.

Relevance to Domestic Intelligence: The act merged agencies such as FEMA, the Secret Service, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) under DHS. A key component of this restructuring was the creation of the DHS Office of Intelligence and Analysis (I&A), tasked with collecting, analyzing, and disseminating intelligence on domestic threats.

Intelligence Gathering: DHS’s intelligence operations focus on domestic terrorism, infrastructure vulnerabilities, and public safety threats. The I&A leverages open-source intelligence (OSINT) and collaborates with state and local entities through Fusion Centers. Despite these efforts, the efficacy of DHS intelligence initiatives has been undermined by systemic flaws.

Dissemination: Fusion Centers were designed to facilitate information sharing between federal, state, and local entities. While these centers have shown promise, failures in dissemination have exposed their limitations. For instance, the delayed sharing of intelligence related to January 6th highlighted ongoing systemic issues, demonstrating that the centralized structure envisioned by the Homeland Security Act has not fully resolved the challenges of interagency communication.

The Privacy Act of 1974

The Privacy Act was established to protect personal information collected by federal agencies and regulate how that information is stored and shared. While designed to balance intelligence gathering with civil liberties, its application has often highlighted systemic tensions between security and privacy.

Relevance to Domestic Intelligence: The act enforces limits on how agencies such as the FBI and DHS can collect, store, and disseminate personally identifiable information (PII). These restrictions aim to ensure that intelligence operations do not infringe on constitutional rights.

Intelligence Gathering: The Privacy Act requires agencies to collect information transparently, ensuring the public knows what data is being gathered and how it will be used. Despite these guidelines, oversight failures have occasionally allowed agencies to skirt transparency requirements.

Dissemination: The Privacy Act prohibits sharing personal information without appropriate safeguards unless it is deemed essential for law enforcement or national security purposes. However, breaches and overreach in dissemination practices have periodically exposed vulnerabilities in this protective framework.

Freedom of Information

FOIA provides the public with the right to access federal agency records, promoting government transparency and accountability. Despite its potential, the law’s effectiveness is often undermined by overuse of national security exemptions.

Relevance to Domestic Intelligence: FOIA has been instrumental in uncovering abuses of intelligence powers and holding agencies accountable for operational failures. Yet, intelligence agencies frequently invoke “national security” to limit disclosure, restricting public oversight.

Dissemination: FOIA forces agencies to justify withholding information, theoretically ensuring a degree of accountability. However, opaque processes and broad exemption claims have diluted its power, leaving critical questions about intelligence practices unanswered.

Why These Laws Matter

These statutes form the backbone of domestic intelligence operations, governing how information is gathered, analyzed, and shared. They are designed to balance national security with civil liberties, but that balance often shifts, especially during crises. Understanding these laws allows citizens to spot failures, demand accountability, and push for reforms where necessary.

So, while it might seem tedious, understanding the specifics of these laws is crucial if we’re serious about achieving transparency and addressing systemic problems in intelligence operations. After all, our republic is supposed to be of the people, by the people, and for the people.

Right?

The relationship between top CIA officers and the shadowy Knights of Malta is cemented in the fact that many Directors of Central Intelligence and other executive level officers are also members of [SMOM] this knightly order.

In fact, membership of the Knights of Malta, also known as SMOM (Sovereign Military Order of Malta) an abbreviation of its full title of The Sovereign Military and Hospitaler Order of St. John of Jerusalem of Rhodes, and American intelligence pre-date the CIA. William (Bill) Donovan, the head of the wartime OSS (Office of Strategic Services) – the precursor to the CIA - was associated with SMOM. As was James Jesus Angleton, the CIA’s hard-core counter-intelligence expert until he was fired by President John Kennedy. Another DCI (Director of Central Intelligence) who was a knight was Bill Casey who was chief of the CIA during the Reagan Administration. Earlier, Bill Colby, who headed the spy agency during the Vietnam War era was approached to become a member but declined. Other senior CIA SMOM Knights included:

William Buckley

John McCone

General Alexander Haig

Perhaps the relationship has something to do with the fact that the Knights of Malta are said to be the Vatican’s own intelligence network. And if one were to seek a Nazi connection to SMOM, just to place matters in historical perspective, it would not be long in coming. Reinhard Gehlen, the former Nazi intelligence supreme who went to work for the CIA immediately after the war and later founded the present day German intelligence agency the BND – the Bundesnachtrichtdienst - was awarded SMOM’s Cross of Merit decoration.

Moreover, Franz von Papen, a Knight Magistral Grand Cross of SMOM, was vital to Hitler’s assumption to power and was soon rewarded for his able assistance by being appointed Ambassador to Austria – an appointment not without considerable significance when it is recalled that Austria was Hitler’s own birthplace. With such high profile Nazi’s being honoured by, or elevated to membership of SMOM, both before and after WWII, it is not difficult to conclude that SMOM’s sense of justice and concern for the ills of the human condition – which it trumpets today as its principal raison d’etre - falls woefully short of accepted norms.

This lays out the constitutional mandate for government at the federal level which is to defend and protect against all enemies, both foreign and domestic. You’re correct ( in my opinion) that some legislation is not in the interest of maintaining power in the hands of the people vs the government. The legislation you described 1946, 1978, 2001 and 2002 was all passed to remove that power a bit at a time and increase control of the citizens…part of a long term effort to ensure we no longer led the world. The US is the final goal due to the rights we still possess, mainly that of keeping weapons, and thus property. What we need to do as citizens is to reinstate our previous position and this will also meet the goal of government without corruption. This must be a public mandate to our representatives.

Great information in this series! Thank you!!