Introduction

The overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii on January 17, 1893, remains a deeply contentious and emotional subject, especially among Native Hawaiians who view it as an illegal act that led to the loss of their sovereignty and rights to self-determination. The involvement of the United States, both at the level of diplomatic and military representatives, adds a layer of complexity to this historical event. It's a chapter in American history that many believe has not been adequately addressed, despite a formal apology from the U.S. Congress in 1993.

The role of the United Church of Christ, formerly known as the Congregational Church, further complicates the narrative. The church, which initially sent missionaries to spread Christianity, later found itself entangled in the political and economic machinations that led to the overthrow. The church's subsequent acknowledgment and apology for its role in these events have been steps toward reconciliation, but they also serve as a reminder of the deep-seated issues that continue to affect Native Hawaiians today. Amidst the backdrop of recent fires that have devastated parts of Hawaii, the historical wounds feel ever more open, making this a critical time for reflection and dialogue.

Historical Background: The Confluence of Factors Leading to the Overthrow

The history of Hawaii is a tapestry woven from the threads of native traditions, foreign influence, and the struggle for sovereignty. It is essential to understand the various elements that converged over time, shaping the destiny of the Kingdom of Hawaii and its people. From the self-sufficient social systems of Native Hawaiians to the arrival of Europeans and Americans, each phase left an indelible mark on the islands. This section delves into the critical aspects that set the stage for the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1893, focusing on the missionary influence, the rise of the sugar industry, the imposition of the Bayonet Constitution, and the Native Hawaiians' struggle for sovereignty.

The Missionary Influence

The United Church of Christ, formerly known as the Congregational Church, holds a pivotal position in the historical tapestry of Hawaii. From 1820 to 1850, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions dispatched over a hundred missionaries to the Hawaiian Islands. Although their primary mission was the propagation of the Christian faith, their impact rippled through various facets of Hawaiian society, including education, governance, and commerce. As the years passed, the progeny of these early missionaries transitioned into influential roles as sugar magnates and financial moguls, amassing considerable clout and affluence.

The Sugar Industry's Rise

The sugar industry became a cornerstone of Hawaii's economy by the mid-19th century. American sugar planters, many of whom were descendants of the early missionaries, gained considerable influence. The Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 was a pivotal moment, as it allowed Hawaiian sugar to enter the U.S. market tax-free. However, this economic boon came at a cost: the treaty permitted the U.S. Navy to use Pearl Harbor, thereby increasing American military presence in the islands.

The Bayonet Constitution

In 1887, King Kalakaua was forced to sign the "Bayonet Constitution," which severely restricted his powers and extended voting rights to wealthy non-Hawaiians, further consolidating American influence. The constitution was named for the intimidating presence of armed militia, which pressured the King into signing it. This event was a precursor to the eventual overthrow, as it weakened the monarchy and empowered foreign interests.

The Struggle for Sovereignty

Throughout these years, Native Hawaiians were not passive observers. They engaged in political and social efforts to maintain their sovereignty and protect their lands. Queen Liliuokalani, who succeeded King Kalakaua, attempted to promulgate a new constitution to restore Native Hawaiian rights and the power of the monarchy. Unfortunately, her efforts were thwarted, setting the stage for the 1893 overthrow.

The Overthrow: A Closer Look at the Forces and Faces Behind the Coup

On January 17, 1893, the Kingdom of Hawaii found itself at a historical crossroads, forever altering its trajectory. Orchestrated by a Committee of Safety, comprising American and European sugar planters and financiers, the overthrow was not a spontaneous act but a calculated move. The Committee had been planning for some time, and their actions were facilitated by the United States Minister to Hawaii, John L. Stevens. He ordered the landing of U.S. Marines from the USS Boston, who positioned themselves near key government buildings, including Iolani Palace.

Queen Liliuokalani, faced with the intimidating presence of armed forces and the potential for bloodshed among her people, made the agonizing decision to yield her authority. However, she did so under protest, explicitly stating that she was surrendering to the "superior force of the United States of America," thereby delegitimizing the Provisional Government set up by the Committee of Safety. Her statement was a political maneuver aimed at highlighting the unlawful nature of the overthrow and the role played by the United States in it.

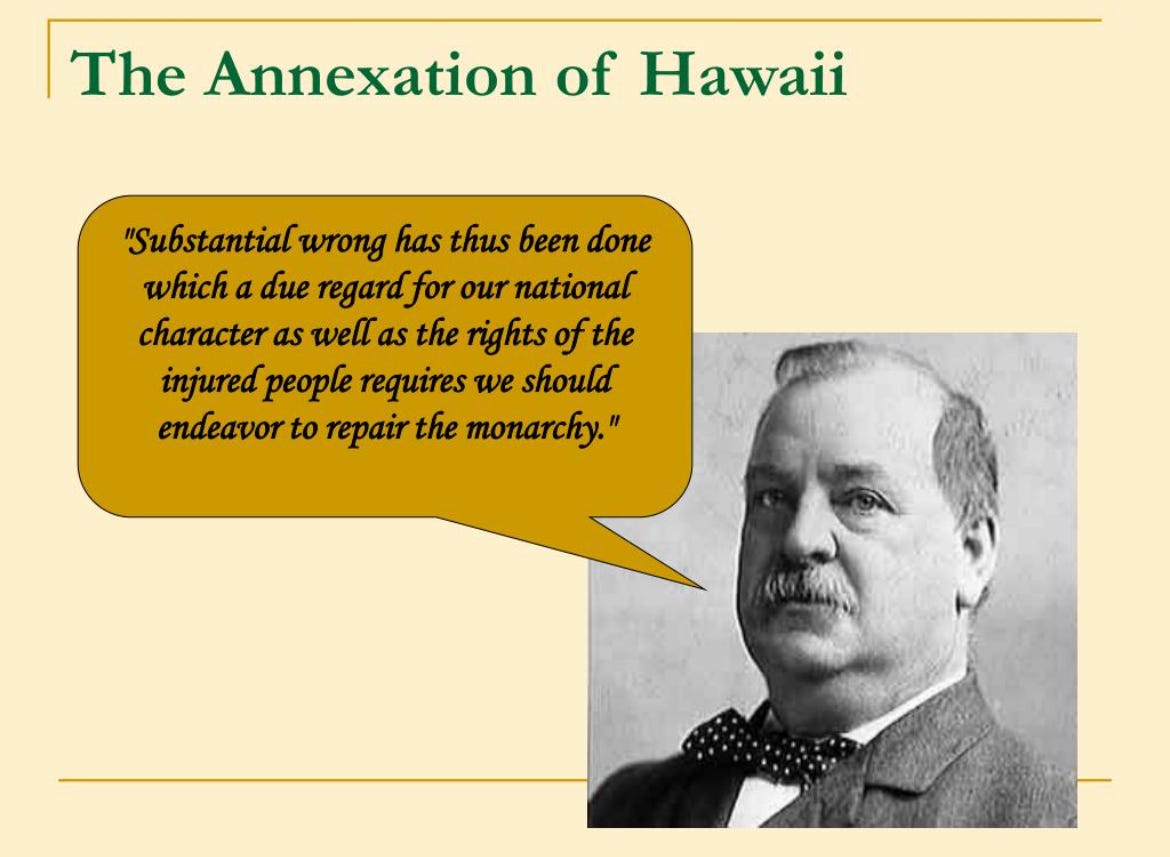

In the immediate aftermath, President Grover Cleveland commissioned an investigation led by former Congressman James Blount. The Blount Report was unequivocal in its findings: the overthrow was illegal, and the U.S. diplomatic and military representatives had overstepped their bounds. Cleveland was inclined to restore the monarchy but faced opposition in Congress and from the newly elected President William McKinley, who was more amenable to annexation.

Despite the Blount Report's damning conclusions, the Provisional Government remained in power and continued to lobby for annexation. They presented their case to the U.S. Senate's Committee on Foreign Relations, skillfully obscuring the U.S. role in the overthrow and advocating for Hawaii's annexation. This lobbying effort was a testament to the political savvy of the Committee of Safety and their allies, who understood the nuances of American politics and were willing to exploit them to achieve their ends.

The Committee of Safety, while primarily composed of American and European sugar planters, also had the tacit support of other influential groups within Hawaii. These included local businessmen and traders who saw potential economic benefits from annexation to the United States. Their collective influence was not merely local but extended to powerful circles within the U.S. government. This network of interests created a formidable force that was both well-organized and well-connected, making it increasingly difficult for Queen Liliuokalani to counteract their moves effectively.

Moreover, the media played a not-so-insignificant role in shaping public opinion during this period. Newspapers, largely controlled by interests sympathetic to the Committee of Safety, portrayed the Queen and her government as corrupt and ineffective. This narrative, which was also disseminated in the United States, helped to create a climate that was more conducive to the idea of annexation. It provided a veneer of legitimacy to the overthrow, painting it as a necessary step towards 'civilizing' Hawaii, in line with the imperialist ideologies prevalent at the time.

The United Church of Christ (UCC) and Its Role in the Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii

The United Church of Christ (UCC), originally known as the Congregational Church, played a significant role in the events leading up to the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii. Between 1820 and 1850, the Congregational Church, through its American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, sent more than 100 missionaries to the Kingdom of Hawaii. While their initial intent was to spread Christianity, the missionaries and their descendants became deeply involved in the political and economic life of the islands.

Over time, the descendants of these missionaries, often referred to as the "missionary party," gained significant influence and power in Hawaii. They became landowners, sugar planters, and financiers. This group was instrumental in the formation of the Committee of Safety, which conspired to overthrow Queen Liliuokalani and the Hawaiian monarchy. The United States Minister to Hawaii, John L. Stevens, who was sympathetic to the missionary party, also played a crucial role in the overthrow.

In 1993, the Eighteenth General Synod of the United Church of Christ acknowledged the church's historical complicity in the illegal overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii. The Synod directed the Office of the President of the United Church of Christ to offer a public apology to the Native Hawaiian people and to initiate the process of reconciliation between the church and the Native Hawaiians.

Thus, the United Church of Christ, through its historical actions and descendants of its missionaries, had a significant impact on the political landscape of Hawaii, contributing to the events that led to the overthrow of the Kingdom. The church's later acknowledgment and apology for these actions represent an attempt at reconciliation and redress.

The United Church of Christ's involvement in Hawaii was not merely a footnote but a significant chapter in the island's history. The church's influence extended beyond the spiritual realm; it permeated the social fabric of Hawaiian society. The missionary party's descendants were not just passive observers but active participants in shaping the political climate. Their influence was so pervasive that they were able to alter the course of Hawaii's history, steering it towards annexation.

The church's role in the overthrow was not an isolated incident but part of a broader pattern of religious institutions being entangled in colonial and imperialistic ventures. This was not unique to Hawaii; similar dynamics played out in other parts of the world where religious missions were often the vanguard of colonial expansion. However, the case of Hawaii stands out because of the church's later acknowledgment of its role, a rare instance where a religious institution has formally admitted to such complicity.

The 1993 acknowledgment by the United Church of Christ's Eighteenth General Synod was more than a symbolic gesture; it was an admission of a historical wrong. This public apology was a step towards mending the fractured relationship between the church and the Native Hawaiians. While it could not undo the past, it served as a catalyst for dialogue and potential reconciliation, opening a path for both parties to navigate the complex terrain of historical injustices and their contemporary implications.

The Aftermath

The annexation of Hawaii through the Newlands Resolution in 1898 and the subsequent territorial status imposed by the Organic Act of 1900 had a profound and lasting impact on the Native Hawaiian population. This act led to the Americanization of Hawaii's legal and educational systems, further diluting Native Hawaiian culture and traditions. The territorial government also promoted the sugar industry, which led to the importation of labor from Asia. This altered the demographic makeup of the islands, adding another layer of complexity to the issue of native rights and identity.

The transition of Hawaii from a U.S. territory to the 50th state of the United States in 1959 did little to alleviate the historical grievances of the Native Hawaiians. While statehood brought about economic development and modernization, it also intensified the commodification of land and natural resources, often to the detriment of Native Hawaiians. The statehood vote itself has been a subject of controversy, as it did not offer the option for Native Hawaiians to express their desire for independence or greater autonomy.

In 1993, the U.S. Congress passed Public Law 103-150, commonly known as the "Apology Resolution," which acknowledged the United States' role in the illegal overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii. The resolution expressed regret for the suppression of the inherent sovereignty of Native Hawaiians. However, the resolution did not provide reparations or a pathway for the restoration of Hawaiian sovereignty, leaving the issue unresolved and a source of ongoing tension.

The Apology Resolution, while a significant acknowledgment, has not translated into tangible benefits or reparations for Native Hawaiians. Various efforts to achieve federal recognition for Native Hawaiians, akin to that of Native American tribes, have been met with political resistance and legal challenges. The absence of federal recognition limits the avenues available for Native Hawaiians to seek redress and hampers their efforts to regain lost lands and cultural heritage.

Moreover, the military's continued presence in Hawaii, particularly the U.S. Pacific Command headquartered at Camp H.M. Smith, serves as a constant reminder of the islands' strategic importance to the United States. This military footprint has environmental, social, and cultural implications, further complicating the relationship between Native Hawaiians and the federal government. The land once used for traditional practices and subsistence is now often restricted or utilized for military exercises, exacerbating the sense of loss and dispossession among Native Hawaiians.

Current Ramifications

The Struggle for Sovereignty and Land Rights

The Native Hawaiian people have never relinquished their claims to inherent sovereignty or their national lands. Various movements and organizations, such as the Office of Hawaiian Affairs and grassroots groups like Ka Lahui Hawaii, have been advocating for Native Hawaiian rights, land restoration, and cultural preservation. The Akaka Bill, named after former U.S. Senator Daniel Akaka, sought to provide a process for Native Hawaiians to gain federal recognition. Although the bill has not been passed, its introduction has sparked a renewed debate over the legal and political status of Native Hawaiians. The absence of federal recognition has significant implications, as it limits the legal avenues available for Native Hawaiians to seek redress for historical injustices.

Environmental Concerns and Natural Disasters

The recent fires in Hawaii have added another layer of complexity and urgency to the situation, serving as a manifestation of long-standing grievances among Native Hawaiians. These fires are not merely environmental disasters; they are a symptom of systemic mismanagement and neglect by authorities. The concept of "malama 'aina," or "to care for the land," is deeply ingrained in Native Hawaiian culture. Many argue that a return to these traditional land management practices could mitigate some of the environmental challenges facing the islands. However, the subsequent response from authorities, including a lackluster visit from the President, has been a source of deep frustration and anger, particularly among Native Hawaiians.

The President's visit, viewed by many as perfunctory and lacking in substantive action, added insult to injury. It's not just a matter of optics; it's a matter of life and death, of homes destroyed and communities uprooted. This inadequacy serves as a stark reminder of the systemic neglect and disregard for Native Hawaiian communities and their unique challenges. The fires have become a political and cultural flashpoint, symbolizing a broader pattern of mismanagement and neglect by authorities. They have ignited debates about the role of traditional Native Hawaiian practices in mitigating such disasters, exposing glaring gaps in current land management policies. There is an urgent need for a paradigm shift that incorporates Native Hawaiian wisdom and expertise.

The President's lackluster visit and the inadequate governmental response to the fires are emblematic of the broader systemic issues that plague the relationship between Native Hawaiians and the federal and state governments. This is not just about the immediate crisis; it's about the long-standing grievances, the historical injustices, and the ongoing struggle for Native Hawaiian rights and sovereignty. The fires and the subsequent response have laid bare the urgent need for a more equitable, inclusive approach to governance that respects Native Hawaiian culture, rights, and expertise. Anything less is not just a failure of policy; it's a failure of justice. The situation calls for a comprehensive reevaluation of how governance and land management are conducted in Hawaii, especially in ways that involve and respect the Native Hawaiian community.

Social and Economic Disparities

Hawaii has one of the highest rates of homelessness and landlessness among Native Hawaiians. The state's high cost of living, coupled with limited economic opportunities, has exacerbated these issues. Many Native Hawaiians feel that their voices are not adequately represented in the political process, leading to policies that do not address their unique challenges. The lack of affordable housing and the commodification of land for tourism and development have further marginalized Native Hawaiians, pushing them to the fringes of society.

Cultural Conflicts: The Mauna Kea Controversy

The ongoing construction of the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) on Mauna Kea, a mountain considered sacred by Native Hawaiians, has been a focal point of protest and controversy. The mountain is not just a place of worship but also a burial ground and a symbol of the Native Hawaiian identity. The construction of the telescope has been seen as a desecration of sacred land and an infringement on Native Hawaiian rights. Protests against the TMT have garnered international attention and have been emblematic of the broader struggle for Native Hawaiian sovereignty and cultural preservation.

Congressional Acknowledgment and Future Prospects

In this context, the Congressional acknowledgement and apology take on added significance but also raise questions about what concrete steps will follow to address the historical injustices and current challenges facing Native Hawaiians. The Apology Resolution of 1993, while a significant acknowledgment, has not led to tangible benefits or reparations. Various efforts to achieve federal recognition have been met with political resistance and legal challenges. The absence of federal recognition limits the avenues available for Native Hawaiians to seek redress and hampers their efforts to regain lost lands and cultural heritage.

The Military Footprint and Geopolitical Considerations

The military's continued presence in Hawaii, particularly the U.S. Pacific Command headquartered at Camp H.M. Smith, serves as a constant reminder of the islands' strategic importance to the United States. This military footprint has environmental, social, and cultural implications, further complicating the relationship between Native Hawaiians and the federal government. The land once used for traditional practices and subsistence is now often restricted or utilized for military exercises, exacerbating the sense of loss and dispossession among Native Hawaiians.

The Quest for Reconciliation and Justice

While the Apology Resolution and other similar initiatives represent steps toward acknowledging past wrongs, they fall short of offering a comprehensive solution to the myriad issues facing Native Hawaiians today. Calls for reparations, land restoration, and federal recognition are growing louder, fueled by a younger generation of Native Hawaiians who are more politically active and conscious of their history. Social media campaigns and international advocacy are amplifying these voices, adding pressure on both state and federal governments to act.

The Role of Education and Cultural Preservation

Efforts are underway to preserve Native Hawaiian culture through education. Schools like the Kamehameha Schools, founded under the will of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, aim to foster cultural understanding and pride among Native Hawaiian youth. However, the challenge remains to integrate this cultural education into the broader educational system to combat the erosion of Native Hawaiian identity.

The Global Context: Indigenous Rights and International Law

The struggle for Native Hawaiian rights is part of a larger global movement advocating for the rights of indigenous peoples. International instruments like the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples provide a framework for the recognition and protection of indigenous rights, including those of Native Hawaiians. However, the application of international law remains a contentious issue, and its effectiveness in bringing about meaningful change is still a matter of debate.

An Unfinished Journey

The current ramifications of the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii and subsequent annexation are a tapestry of complex, interwoven issues that defy easy solutions. As Native Hawaiians continue to navigate the challenges of the 21st century, the quest for justice, sovereignty, and cultural preservation remains an ongoing journey, fraught with obstacles but also ripe with possibilities for meaningful change.

Congressional Acknowledgment and Apology

The 1993 Congressional acknowledgment and apology, known as Public Law 103-150 or the "Apology Resolution," was a watershed moment in the complex relationship between the United States and Native Hawaiians. While the resolution was a formal acknowledgment of the United States' role in the illegal overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii, it was largely symbolic. It did not include provisions for reparations, the restoration of Native Hawaiian sovereignty, or any actionable steps to redress the historical injustices inflicted upon Native Hawaiians.

The resolution did express a commitment to acknowledging the ramifications of the overthrow to provide a foundation for future reconciliation. However, this has not translated into significant policy changes or actionable outcomes. Native Hawaiians continue to push for federal recognition and reparations, including the return of ceded lands. These efforts have met with resistance at both the state and federal levels, rendering the apology hollow in the eyes of many. The resolution urging the President of the United States to support reconciliation efforts has been met with varying degrees of commitment from successive administrations, but none have taken decisive action to redress past and ongoing injustices.

The apology is seen by many as a mere performative act without concrete actions to back it up. It's akin to acknowledging a debt but refusing to pay it. For many Native Hawaiians, the apology has only served to stir up more hostility and resentment. It's a reminder of the unfulfilled promises and the deep-seated injustices that continue to plague their community. The absence of reparations and the lack of a pathway to sovereignty have only exacerbated the sense of betrayal. The apology, in this context, becomes not an act of reconciliation but an act of reiteration—reiterating the same power dynamics, the same neglect, and the same systemic inequalities that led to the overthrow in the first place.

The apology also raises ethical and moral questions about the role of the United States in addressing historical wrongs. Can an apology, devoid of reparative action, ever be sufficient? The answer, for many Native Hawaiians, is a resounding no. An apology without action is an empty gesture; it's a band-aid solution to a deeply rooted, systemic issue. It's a failure not just of policy but of moral integrity. The apology has become a symbol of the United States' unwillingness to confront its own history and take meaningful steps to rectify its wrongs. It's a glaring example of how the rhetoric of reconciliation can be co-opted to perpetuate the status quo, rather than challenge it.

In the final analysis, the 1993 Congressional apology serves as a case study in the limitations of symbolic gestures in the face of systemic injustices. It highlights the urgent need for a more comprehensive approach to reconciliation—one that includes not just words but actions; not just acknowledgment but redress; not just promises but fulfillment. Until then, the apology remains a hollow gesture, a token acknowledgment that serves to placate rather than empower. It's a missed opportunity to right historical wrongs and pave the way for a more equitable future. It's a glaring testament to the deep-seated complexities and challenges that continue to impede the path to justice and reconciliation for Native Hawaiians.

Conclusion

The 100th anniversary of the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii serves as a poignant reminder of a complex and painful history. The Congressional acknowledgment and apology, while significant, have not resolved the underlying issues that continue to affect the Native Hawaiian community. The recent fires in Hawaii add a layer of urgency to these longstanding grievances. As the United States grapples with its own history of colonization and injustice, the situation in Hawaii serves as a case study in the complexities of reconciliation and redress. While the apology is a step in the right direction, much work remains to be done to truly reconcile with the Native Hawaiian people and address the challenges they face today.

The fires currently ravaging parts of Hawaii underscore the urgency of addressing these historical and current issues. They serve as a stark reminder that the land and the people are deeply interconnected, and that the unresolved legacy of the overthrow continues to have real and devastating consequences. In this somber context, the need for meaningful reconciliation and actionable solutions has never been more apparent. The 100th anniversary is not just a moment for reflection but also a call to action to address the deep-seated issues that continue to divide and affect the Native Hawaiian community.

The irony of the United States' role in Hawaii is not lost on those who view the nation as a supposed beacon of light, righteousness, and justice. The United States, which often positions itself as a defender of democracy and human rights on the global stage, orchestrated the overthrow of an indigenous monarchy for strategic and economic gain. This glaring contradiction exposes the chasm between the ideals the United States professes and the actions it undertakes. It's a dissonance that reverberates through the corridors of history and into the present day, casting a shadow over the nation's moral and ethical standing.

The United States' actions in Hawaii stand in stark contrast to the principles of self-determination and sovereignty that the nation champions elsewhere. The overthrow and subsequent annexation were not just acts of political and military maneuvering; they were acts that violated the very principles that the United States claims to uphold. It's a betrayal not just of the Native Hawaiian people but of the foundational ideals that the United States purports to represent. This betrayal is compounded by the fact that the Congressional apology, while acknowledging the wrongs committed, has not led to any substantive change or reparations. It's an acknowledgment without accountability, a confession without penance.

The United States' role in Hawaii is a blemish on its historical and moral record, one that calls into question its credibility as a global leader in human rights and justice. It's a cautionary tale that underscores the dangers of unchecked power and the perils of sacrificing principles for strategic interests. It's a lesson in the complexities and contradictions that often accompany efforts to reconcile with a painful past. And it's a wake-up call for the need for a more honest, more equitable approach to addressing historical injustices.

As the United States navigates its complex history and its role on the global stage, the situation in Hawaii serves as a litmus test for the nation's commitment to justice, equality, and human rights. The 100th anniversary of the overthrow, the ongoing struggles of the Native Hawaiian community, and the recent fires are not just events to be commemorated or crises to be managed; they are opportunities for reflection, reckoning, and, most importantly, action. They are moments that challenge the United States to live up to its professed ideals, to bridge the gap between its actions and its aspirations, to transform its apology into a commitment, and to turn its acknowledgment into action.

The path to reconciliation is fraught with challenges, but it's a path that must be walked with sincerity, humility, and a commitment to justice. It's a journey that demands more than just words; it requires actions that reflect the gravity and complexity of the issues at hand. It's a process that calls for a collective effort to right the wrongs of the past and pave the way for a more equitable, more just future. And it's an endeavor that tests the very soul of the nation, challenging it to reconcile not just with the Native Hawaiian community but with its own ideals, principles, and identity.

In conclusion, the Congressional apology, the 100th anniversary of the overthrow, and the recent fires in Hawaii are not isolated incidents but interconnected events that reveal the deep-seated issues that continue to plague the Native Hawaiian community and challenge the United States' moral authority. They are stark reminders of the urgent need for a comprehensive approach to reconciliation—one that goes beyond mere acknowledgment and delves into the realm of tangible, meaningful action. Anything less would be a disservice to the Native Hawaiian community and a betrayal of the ideals that the United States claims to uphold.

Written By SpartanAltsobaPatriot - 17th SOG

Special thanks to an awesome Patriot, Jeremiahbullfrog. veteran researcher and a true humble human being, a mentor to many in this movement, never does anything for recognition, but for the good of our country! It’s an honor knowing you and thanks for the help with the research and for trusting me with this project!

Thank you for this-- very enlightening. I have never been to HI and was unaware of much of the history. I appreciate your lesson and opening my eyes to this injustice.

Right on! The DCCP *stole* them (as far as We The People are concerned in US Constitution 1.8.17), so they are not "our island possessions" and this goes a lot further than just Hawaii. How does our DCCP (D.C.Communist Party) take 'possession' of people and their faraway islands? Tactical Civics™ deals with this too.